At hearing for years-old digital snooping case, EFF and DOJ lawyers face off.

by Cyrus Farivar

OAKLAND, Calif.—A federal judge spent over four hours on Friday questioning lawyers from the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and from the Department of Justice in an ongoing digital surveillance-related lawsuit that has dragged on for more than six years.

During the hearing, US District Judge Jeffrey White heard arguments from both sides in his attempt to wrestle with the plaintiffs’ July 2014 motion for partial summary judgment. He went back and forth between the two sides, hearing answers to his list of 12 questions that were published earlier this week in a court filing.

That July 2014 motion asks the court to find that the government is "violating the Fourth Amendment by their ongoing seizures and searches of plaintiffs’ Internet communications." The motion specifically doesn’t deal with allegations of past government wrongdoing, nor other issues in the broader case.

The case, known as Jewel v. National Security Agency (NSA), was originally brought by the EFF on behalf of Carolyn Jewel, a romance novelist who lives in Petaluma, California, north of San Francisco. For years, the case stalled in the court system, but it gained new life after the Edward Snowden disclosures last summer.

In the 2008 original complaint (PDF), Jewel and the other plaintiffs alleged that the government and AT&T were engaged in an "illegal and unconstitutional program of dragnet communications surveillance conducted by the National Security Agency and other Defendants in concert with major telecommunications companies." The evidence stemmed from materials leaked by former San Francisco AT&T technician Mark Klein in 2006. As Jewel was and remains an AT&T customer, her communications were intercepted by the company on behalf of the NSA, her attorneys argue.

What if the government searched via drone?

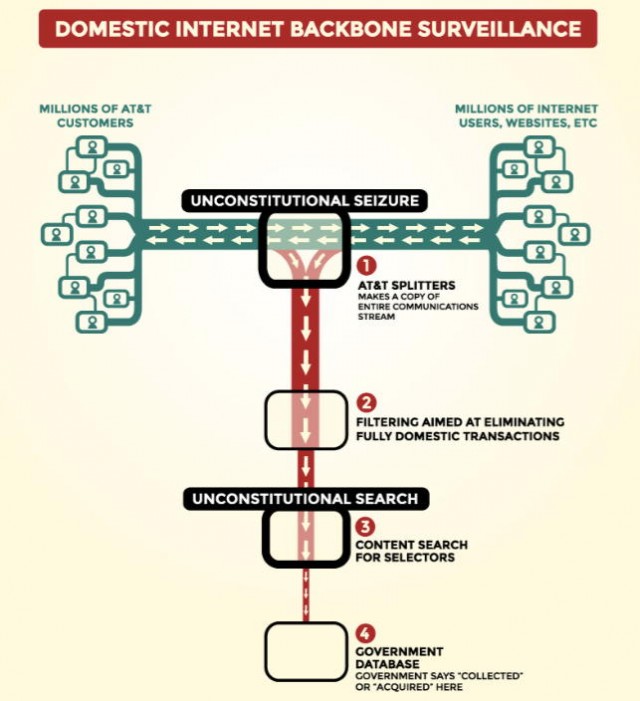

Much of the language invoked by both sides revolves around what the EFF has called a four-stage process as illustrated in the July 2014 motion (as shown above).

Richard Wiebe, one of the plaintiffs’ lawyers, countered: "The government can't circumvent the Fourth Amendment simply by automating its searches and seizures."

"If suddenly our homes were being searched by drones, that wouldn't be permissible under the Fourth Amendment?" he added later.

"What really matters is not what the government gains but what the plaintiffs lose: they lose privacy and control of their communications. That's really what we're talking about. The Fourth Amendment protects us all against mass surveillance of our papers."

Eventually, Wiebe concluded:

That rule would apply equally to the Oakland Police Department as it would to the NSA? If there's no search and no seizure there's no Fourth Amendment scrutiny. It means that all of our communications could be monitored for crime. Once that evidence was found that info could be sequestered without further review, they could use the knowledge that was in it to get probable cause to look into the communications. It's a complete backdoor into all of our communications.Buzz off

Among other things, the government argued that the plaintiffs lack standing and simply cannot prove that their communications were necessarily captured, and therefore they are entitled to file a claim.

"[Plaintiffs] don’t even know the communications exist because they are electronically scanned and having been found not to have targeted selectors are destroyed in a flash before any human review," James Gilligan, a Department of Justice attorney, told the court.

The government further defended itself on multiple fronts, arguing that some of the evidence presented by the plaintiffs is inadmissible in court. For example, one item that the government wanted to not be considered is Klein’s declaration about the secret room at an AT&T facility in San Francisco.

"[Klein] has no first knowledge of what occurred in the SG3 room," Gilligan said. "[In his declaration], in which he states that he did not work in there and except on one brief occasion, he never even set foot in that room, so he cannot attest from personal knowledge on what was installed there or what was used there. Without evidence that the equipment was installed there: his opinions as to the capabilities are irrelevant."

Most broadly, Gilligan forcefully argued that the testimony provided by Klein and others was "hearsay and speculation."

"And also it concerns alleged events 10 to 12 years ago—it's far, far too remote in the field of analysis to be probative to anything that's occurring today," he said.

Further, the plaintiffs also cited a National Security Agency Inspector General’s report that was published by The Guardian as part of the Snowden disclosures.

Gilligan dismissed that too: "What Wiebe is referring to is a document that was posted by The Guardian, the government has never confirmed or denied it to be the case. It is wholly unauthenticated."

Over a month before the hearing, the government also submitted a written declaration by one "Miriam P.," who describes herself as the Deputy Chief of Staff for Signals Intelligence Policy and Corporate Issues for the Signals Intelligence Directorate (SID) of the National Security Agency.

Judge White, who raised the possibility of dismissing the case but included a classified opinion given the nature of the case, is expected to rule on the motion in the coming months.

No comments:

Post a Comment