Persistent Surveillance Systems can watch 25 sq. miles—for hours.

by Cyrus Farivar

On June 28, 2012, in Dayton, Ohio, police received reports of an attempted robbery. A man armed with a box cutter had just tried to rob the Annex Naughty N’ Nice adult bookstore. Next, a similar report came from a Subway sandwich shop just a few miles northeast of the bookstore.

Coincidentally, a local company named Persistent Surveillance Systems (PSS) was flying a small Cessna aircraft 10,000 feet overhead at the time. The surveillance flight was loaded up with specialized cameras that could watch 25 square miles of territory, and it provided something no ordinary helicopter or police plane could: a Tivo-style time machine that could watch and record movements of every person and vehicle below.

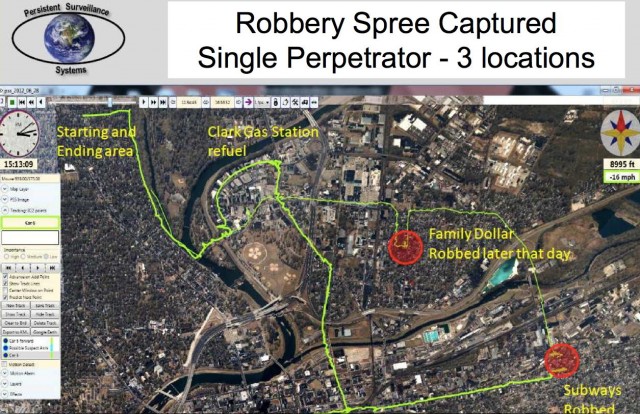

After learning about the attempted robberies, PSS conducted frame-by-frame video analysis of the bookstore and sandwich shop and was able to show that exactly one car traveled between them. Further analysis showed that the suspect then moved on to a Family Dollar store in the northern part of the city, robbed it, stopped for gas—where his face was captured on video—and eventually returned home.

A man named Joseph Bucholtz was arrested the following month and pled guilty to three counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon and one count of robbery. In November 2012, he was sentenced to five years in prison and ordered to pay $665 to the bookstore.

Though an all-seeing, always recording eye in the sky might sound dystopian, current PSS surveillance tech has real limitations. For now, the cameras can only shoot for a few hours at a time, only during the day, and sometimes just in black-and-white. When watching from 10,000 feet, PSS says that individuals are reduced to a single pixel—useful for tracking movements but not for identifying someone.

“You can’t tell if they’re red, white, green, or purple,” Ross McNutt, the company’s CEO, told Ars. And even if the half-meter resolution on his cameras got significantly better, McNutt said that he would prefer to fly higher and capture a larger area.

McNutt wants to be sensitive to people’s concerns, and PSS meets with the ACLU and other privacy activists as such. But he also wants to catch criminals. McNutt, who helped develop the technology when it was a military research project at the nearby Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT) back in 2004, claims that his system has already proved its value. A visual timeline of the Bucholtz case has been used numerous times in PSS presentations, but McNutt said that his cameras have seen far worse.

"We have witnessed 34 people being murdered within our imaged areas and been able to track people to and from those scenes," he said. "The people who confessed on being captured with assistance from our imagery confessed for a total of 75 murders. Many of the people confessed once captured to many more murders than we tracked them to."

Much of the company's work has actually come from Mexico, where PSS helped make the most of its "significant captures." (The company's work there "was done very quietly to protect us and our customer from retribution," McNutt adds.)

Now, after years of short-term contracts, the retired Air Force Lieutenant Colonel is lobbying 10 US cities—he won’t name them, apart from Chicago—for longer contracts. He’s also dangling a sizable carrot in front of them: a new analysis center that would have “hundreds” of jobs and would act as a command center for all of the company’s operations nationwide.

Despite past efforts in cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Cleveland and at events like the 2014 Indianapolis 500 car race, PSS says it currently has no active contracts inside the United States. McNutt is increasingly mystified at cities that won’t hire his eye-in-the-sky surveillance firm.

“We have hundreds of politicians that say crime is their number one issue, and no it’s not,” McNutt said. “If it was true, they wouldn’t stand for 36,000 crimes a year (per city), worth a $1 billion a year. It shows up in lower housing prices and it shows in people not wanting to move there. If you could get rid of the crime stigma you would see house prices rise and businesses move there. I am frustrated that politicians don’t have the leadership to do it.”

That's in part because tech like this—to put it bluntly—creeps people out.

Straight over Compton

Consider Compton, a city just south of downtown Los Angeles. In 2012, PSS ran a nine-day test there under the authority of the Los Angeles Sheriff's Department—without notifying Compton city officials.

When news of the test was reported earlier this year by the Center for Investigative Reporting and the Los Angeles Times, Compton's mayor was upset, and the cops admitted they concealed the experiment because citizens were sensitive about surveillance.

"The system was kind of kept confidential from everybody in the public," project supervisor, Los Angeles County Sheriff Sgt. Doug Iketani, told the Center for Investigative Reporting. "A lot of people do have a problem with the eye in the sky, the Big Brother, so in order to mitigate any of those kinds of complaints, we basically kept it pretty hush-hush."

The Sheriff's Department then proceeded to dump on PSS and its tech, saying it hadn't worked well anyway. As an April 2014 press release put it:

The evaluation found the system would not enhance the capabilities of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and all equipment was removed by Persistent Surveillance Systems.McNutt scoffs at these statements. "We did 30 investigations; we contributed to a whole bunch of takedowns,” he told Ars. “They were downplaying it in part because of the issues. They said that they kept it hush-hush. We briefed a lot of folks. We briefed the sheriff’s office and various politicians and asked them to come down and see it while we were there. The head of the Aero Bureau said: ‘You guys are the future of airborne law enforcement.’ We know it had an impact. We had nice feedback from them.”

Sheriff’s Aero Bureau and Compton Sheriff’s personnel identified a number of challenges that rendered the system ineffective for the Department’s need to enhance public safety and impact criminal activity. The factors included the resolution of the video footage captured did not offer any detail which would allow the identification of any individual. The detail provided would not allow the reviewer of the footage to discern gender, age, race, hair color, or any other identifiable features. Another factor was that it was difficult to identify the difference between a sub-compact vehicle and a full-sized sports utility vehicle. Another decision not to pursue the use of the system was the fact that the footage could only be captured in black and white.

But the situation has made the PSS tech a more difficult sell, even in its own backyard.

Nothing to hide?

One of the biggest PSS cheerleaders has been Richard Biehl, police chief of Dayton, Ohio—where PSS is based.

As recently as March 14, 2014, according to e-mails obtained by Ars, Biehl signed his name to a letter drafted by Robert Casebere, a PSS vice president. The letter went to a potential client, the security minister of murder-plagued Honduras, and it stated:

We found their systems and services to be a significant asset to our officers to detect and investigate criminal events. It is my belief that through consistent use, this system will ultimately reduce and deter crime.This was because, in Biehl's telling, 2012 test flights from PSS proved valuable. As he wrote:

On several occasions, the use of the system assisted with apprehension of suspects involved in serious crimes. On one such occasion, an individual committed a robbery offense at three separate commercial locations on the same day. Through the forensic analysis of the captured data, PSS was able to recreate the route the offender drove to each of the locations, which provided valuable information to our investigators.E-mails that Ars obtained via a public records request show that representatives from Honduras, Brazil, Thailand, the Netherlands, and Russia have all come to Dayton over the last two years to observe demonstrations held by PSS, often with the attendance and endorsement of the Dayton Police Department.

“Surveillance is part of the current and future,” Shelley Dickstein, the Dayton assistant city manager, told Ars. “If it can be used and managed for the collective good, then I think that there is great value there.”

Although Dayton declined to sign a 200-hour contract in Spring 2013—partly due to political pushback and partly due to expense—the city has maintained cordial relations with PSS. As recently as May 2014, Mayor Nan Whaley convened a meeting with various community groups and privacy activists at the PSS offices to discuss future work with PSS.

“I walked away [from that meeting] saying we’re way ahead of the culture right now, and there has to be a lot more socializing of this idea of surveillance and we have to get a lot further along of the utility of the data and the guidelines that go with that,” Dickstein said. “I don’t have any qualms about being surveilled because I’m not doing anything wrong. If it means that unlawful citizens get stopped—I don’t have anything to hide from.”

"Round the clock surveillance of citizens"

Claiming that you "have nothing to hide" is not an argument that moves Joel Pruce, a lecturer and post-doctoral fellow in Human Rights Studies at the University of Dayton. He has been one of the local activists leading the charge against PSS.

“We just came to the decision that there is no viable way to lawfully protect the civil liberties of privacy rights in Dayton with persistent surveillance,” Pruce told Ars. “We weren’t convinced that this was just a test product. You need a warrant to tap [someone’s] phone or to follow people. There is no way to protect rights and liberties with surveillance that is persistent.”

Pruce noted that Dickstein’s experience with law enforcement—particularly as a white, well-educated, professional city employee—may be far different from other parts of the city. There’s another side of the city entirely where the residents tend to be non-white, tend to live in greater levels of poverty, tend to have more frequent (and often harsher) interactions with the police, and tend to be far more skeptical of police power.

“The primary concerns when it comes to arguments like that is surveillance in American history has disproportionately targeted communities of color and political dissidents,” Pruce said. “For Ms. Dickstein to say that [she has nothing to hide]—if she’s not concerned that’s up to her. We heard from people in other neighborhoods that would be concerned... When you talk to people in those communities, they say that surveillance is not the relationship that we want to have with the police.”

He fears that, in particular, such monitoring—despite the best-intended policies that claim the contrary—will be used to keep tabs on political protests and other First Amendment-protected activities.

Gary Daniels, a chief lobbyist with the ACLU Ohio and a strong opponent of PSS’ deployment in Dayton, said that for the time being PSS has been stymied largely because the technology remains unproven.

Further Reading

Footage shows cop ran a stop sign but arrested a sober victim for drunken driving.“Government entities generally don’t like to be the first to do anything,” he said. “They like there to be some track record so they can evaluate. Here we have no real track record.”

While the ACLU is generally in favor of surveillance technologies that have precise limitations, it opposes most blanket coverage of citizens.

“When you surveil everybody all of the time, I can’t figure out any way to regulate that in a way that takes care of significant privacy,” Daniels said.

“To their credit they want to be transparent, they want to work with ACLU on ordinances or procedures to regulate so long as it allows them to keep selling, but the problem is: there’s a gap here that can’t be lessened. Look, the technology itself is unacceptable when used by the government. There’s no way to call it anything than what it is: round the clock surveillance of citizens. Once you give the government a little bit of power, it doesn’t stop there. I think at some point you will have some city or state that signs up for this.”

Wanted: First-person shooter fans

McNutt insists that PSS has safeguards in place to protect privacy and prevent abuse, and he says that he’s never experienced any inappropriate behavior by his pilots or his analysts.

“I can tell you everywhere my analysts have ever looked,” he said. “I can tell you every place and every time my analysts have looked and who looked at it. I can tell whether they’re doing investigations or whether they’re looking at their girlfriend's house. That hasn’t been a problem as they typically don’t have girlfriends in those areas.”

In the meantime, McNutt continues to hire analysts—and he prefers them to be gamers.

“The biggest requirement I have is that they play video games,” he said. “If they can do a first-person shooter, they can track cars really well. I can teach them how to do investigations, PowerPoint, and brief the officers on what they saw. Then the only problem is that then I lose them to military intelligence that pay four to five times better a few years later.”

Despite the fact that so many American cities are interested in deploying surveillance tools like stingrays and license plate readers on a massive scale, there appears to be limited appetite for the PSS tech. McNutt remains baffled that American cities haven’t yet signed longer-term, $2,000-per-hour contracts with his firm—but the lobbying efforts continue.

No comments:

Post a Comment