For years the U.S. military has been waging a biometric war in Afghanistan, working to unravel the insurgent networks operating throughout the country by collecting the personal identifiers of large portions of the population. A restricted U.S. Army guide on the use of biometrics in Afghanistan obtained by Public Intelligence provides an inside look at this ongoing battle to identify the Afghan people.

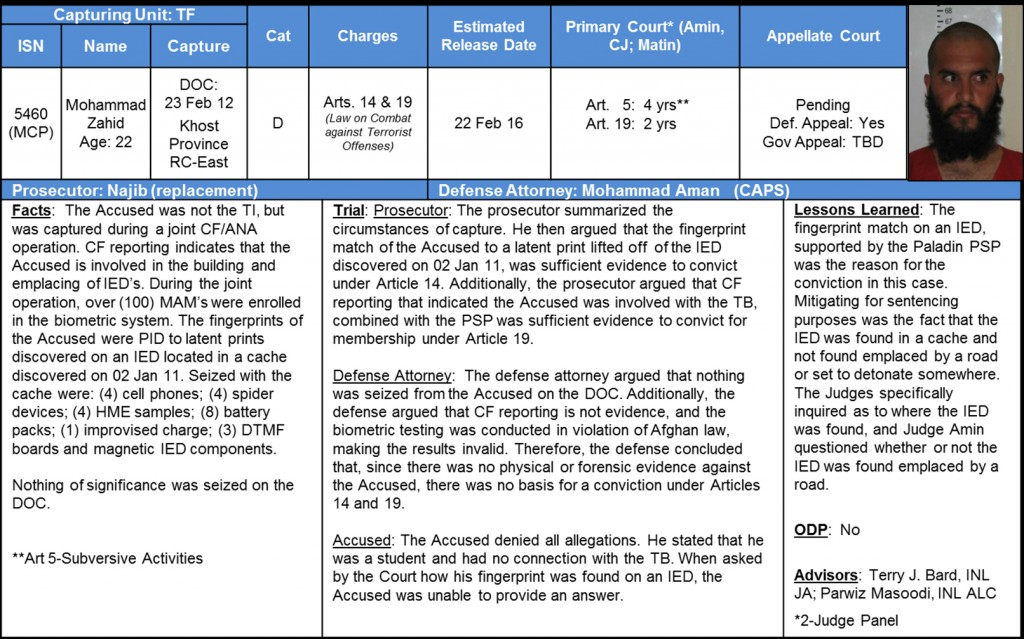

Mohammad Zahid was not the target of a joint military operation that came through his village in Khost Province in late February 2012. However, that day the twenty-two year old man who claimed to be a student was arrested and eventually convicted in an Afghan court because his fingerprints reportedly matched those found on an improvised explosive device (IED) cache that had been discovered the previous year.

Zahid was one of more than a hundred military-age males that were scanned that day by the joint coalition forces and Afghan National Army operation. As part of its effort to combat insurgent forces interspersed within an indigenous population, the use of biometrics has become a central component of the U.S. war effort. Having expanded heavily since its introduction during the war in Iraq, biometric identification and tracking of individuals has become a core mission in Afghanistan with initiatives sponsored by the U.S. and Afghan governments seeking to obtain the biometric identifiers of nearly everyone in the country.

Though there is no formal doctrine or universally accepted tactics, techniques, and procedures for using biometrics throughout the U.S. military, a 2011 U.S. Army handbook and several other documents obtained by Public Intelligence provide insight into the practical use of biometrics in Afghanistan, showing both the level of collection and the functional use of the data for intelligence gathering, force protection and even obtaining criminal convictions. By collecting vast amounts of information on the population of Afghanistan, including both friend and foe alike, the U.S. military has sought to achieve identity dominance by undermining the fluid anonymity of terrorist and criminal networks and attaching permanent identities to malicious actors.

What is biometrics?

While the use of biometrics has become an increasingly important part of the war in Afghanistan, there is a fundamental lack of agreement about the doctrine surrounding the collection and use of biometric information. An introduction to the 2011 U.S. Army Commander’s Guide to Biometrics in Afghanistan states that there is “no formal doctrine; universally accepted tactics, techniques, and procedures; or institutionalized training programs across the Department of Defense” for biometric capabilities. Despite this lack of formal doctrine, the U.S. military is currently using more than 7,000 devices to collect biometric data from the Afghan population. Though biometrics can take the form of any “measurable biological (anatomical and physiological) and behavioral characteristic that can be used for automated recognition,” the biometric identifiers being collected in Afghanistan consist primarily of fingerprints, iris scans and facial photographs. Other biological characteristics, which are referred to as modalities, that can be used to identify a person include certain types of voice patterns, palm prints, DNA, as well as behavioral characteristics such as gait and even keystroke patterns on a keyboard.

The U.S. military currently uses three devices for collecting the bulk of the biometric data harvested in Aghanistan: the Biometrics Automated Toolset (BAT), Handheld Interagency Identity Detection Equipment (HIIDE) and Secure Electronic Enrollment Kit (SEEK). The BAT is used primarily by the Army and Marine Corps and consists of a laptop computer and separate peripherals for collecting fingerprints, scanning irises, and taking photographs. The HIIDE is more mobile, providing a handheld device capable of collecting fingerprints, scanning irises and taking photographs. Like the BAT, the HIIDE can connect to a network of approximately 150 servers throughout Afghanistan to upload and download current biometric information and watchlists. The SEEK is also a handheld device with many of the same capabilities of the HIIDE, though it also has a built-in keyboard for remotely entering biographical information on the subject. Used primarily by special operations forces, the SEEK will eventually replace the HIIDE as the standard collection device for the Army and Marine Corps.

Airman 1st Class Michael Vue, 455th Expeditionary Security Forces Squadron entry controller, scans an Afghan woman’s iris in the waiting area of the Egyptian Hospital at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, on April 16. Medical teams use biometrics to identify and track the records for all incoming patients by scanning their iris and fingerprints and then inputting the information into a database. Photo via U.S. Air Force.

Data from these devices is stored in local and national databases which can be searched and compared with other intelligence information to help identify enemy combatants. All biometric data collected in Afghanistan is ultimately sent back to the DOD’s Automated Biometric Identification System (ABIS) located in West Virginia, where it is stored and also shared with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and FBI. Partnerships with other nations also allow the DOD to run data against biometrics collected by foreign governments and law enforcement.

Enroll Everyone

Though the use of biometrics is relatively new for U.S. forces, collection efforts in Afghanistan have become ubiquitous, taking in data on large swaths of the population from government officials to local villagers. In 2009, it was reported that even foreign journalists covering the war in Afghanistan would be required to provide their biometric data before being accredited and provided access to military facilities. The collection of biometric data is viewed as being so essential to the war effort that the Afghan Ministry of Interior was enlisted to help run a program called Afghan 1000, which provides a comprehensive framework for collecting biometric data on the citizens of Afghanistan. The program established a goal of enrolling eighty percent of the country’s population by 2012, covering nearly 25 million people. While the actual enrollment numbers are not public, the Afghan 1000 program has been in operation for several years, collecting data for every traveler passing through Kabul International Airport, border crossings and Afghan Population Registration Department offices throughout the country.

The stated goal of the Afghan effort is no less than the collection of biometric data for every living person in Afghanistan. At a conference with Afghan officials in 2010, the commander of the U.S. Army’s Task Force Biometrics Col. Craig Osborne told the attendees that the collection of biometric data is not simply about “identifying terrorists and criminals,” but that “it can be used to enable progress in society and has countless applications for the provision of services to the citizens of Afghanistan.” According to Osborne, biometrics provide the Afghan government with “identity dominance” enabling them to know who their citizens are and link actions with actors. “Your iris design belongs only to you and your left and right irises are different,” Osborne said at the conference. “A name can be changed or altered illegally or even legally, but once your iris is formed at the age of six months, it cannot be altered, duplicated or forged.”

The U.S. Army Commander’s Guide to Biometrics in Afghanistan recommends that “all combat outposts and checkpoints throughout Afghanistan make it a priority to collect biometric data from as many local nationals as possible.” During cordoning operations, the guide advises soldiers to “enroll everyone” including the dead, from which DNA is often collected using buccal swabs to capture the cells that line the mouth. While Afghanistan offers “an extraordinarily complicated environment for the broad employment of biometrics,” the guide notes that the “payoff to U.S. and coalition forces is so great in terms of securing the population and identification of bad actors in the country, that commanders must be creative and persistent in their efforts to enroll as many Afghans as possible.”

U.S. Army Spc. Robert Irwin, serving with 2nd Platoon, D Company, 3rd Battalion, 509th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, Task Force Gold Geronimo, uses his Handheld Interagency Identity Detection Equipment (HIIDE) to scan a local Afghan man’s fingerprints, Paktya Province, Afghanistan, Jan. 30, 2012. Photo via U.S. Army.

In a section titled “Population Management,” the U.S. Army’s guide recommends that “every person who lives within an operational area should be identified and fully biometrically enrolled with facial photos, iris scans, and all ten fingerprints (if present).” The soldiers must also record “good contextual data” about the individual such as “where they live, what they do, and to which tribe or clan they belong.” According to the guide, popuation management actions “can also have the effect of building good relationships and rapport” by sending the message that the “census” is intended to protect them from “the influence of outsiders and will give them a chance to more easily identify troublemakers in their midst.” A checklist included in the section includes the following instructions:

Widespread enrollment of the population or the “census” as the guide refers to it, is seen in Afghanistan “as supportive of the local government, particularly if accompanied with a badging program that highlights the government’s presence in an area.” Tribal leaders and clan heads can use biometrics to control their local area which can lend “authority to tribal leadership by helping them keep unwanted individuals out of their areas.”

- Locate and identify every resident (visit and record every house and business). At a minimum, fully biometrically enroll all military-age males as follows:

- Full sets of fingerprints.

- Full face photo.

- Iris scans.

- Names and all variants of names.

- BAT associative elements:

- Address.

- Occupation.

- Tribal name.

- Military grid reference of enrollment.

- Create an enrollment event for future data mining.

- Listen to and understand residents’ problems.

- Put residents in a common database.

- Collect and assess civil-military operations data.

- Identify local leaders and use them to identify the populace.

- Use badging to identify local leaders, and key personnel.

- Cultivate human intelligence sources.

- Push indigenous forces into the lead at every possible opportunity.

- Track persons of interest; unusual travel patterns may indicate unusual activities.

Biometric Watch Lists

One of the most essential products of the widespread collection of biometric data in Afghanistan is the Biometric Enabled Watch List (BEWL). Known as “the watch list,” the BEWL is a “collection of individuals whose biometrics have been collected and determined by [biometrics-enabled intelligence (BEI)] analysts to be threats, potential threats, or who simply merit tracking.” When loaded onto a biometrics collection device like the HIIDE, the BEWL “allows for instantaneous feedback on biometrics collections without the need for real-time communications to the authoritative biometrics database,” allowing the soldier to immediately identify persons of interest.

Once BEI analysts combine all of the data from biometric enrollments, forensic evidence, and other forms of intelligence they develop the BEWL in cooperation with numerous other intelligence agencies and organizations throughout the government. At least twenty-nine dedicated BEI analysts located throughout Afghanistan work to create the BEWL and individual units can request that specific individuals be added or removed from the list. When a person’s biometric data is collected in Afghanistan and they are not matched to an entity on the watch list, the data and “associated contextual information required for enrollment” are transmitted back to the ABIS in West Virgina for matching against all other collected biometrics, including the 90 million fingerprint entries collected by DHS and 55 million from criminal enrollments made by the FBI. If a match is found there, the information is sent to the National Ground Intelligence Center (NGIC) in Charlottesville, VA which generates a biometrics intelligence analysis report (BIAR) detailing the history and potential threat posed by the individual. NGIC then contacts Task Force Biometrics in Afghanistan which notifies the proper unit in the operational environment. Depending on the unit collecting the biometric data, this process can take anywhere from a few minutes to several days if the match is made against a latent fingerprint. Whether a match is ultimately found or not, all information is stored for further use in the BEI process.

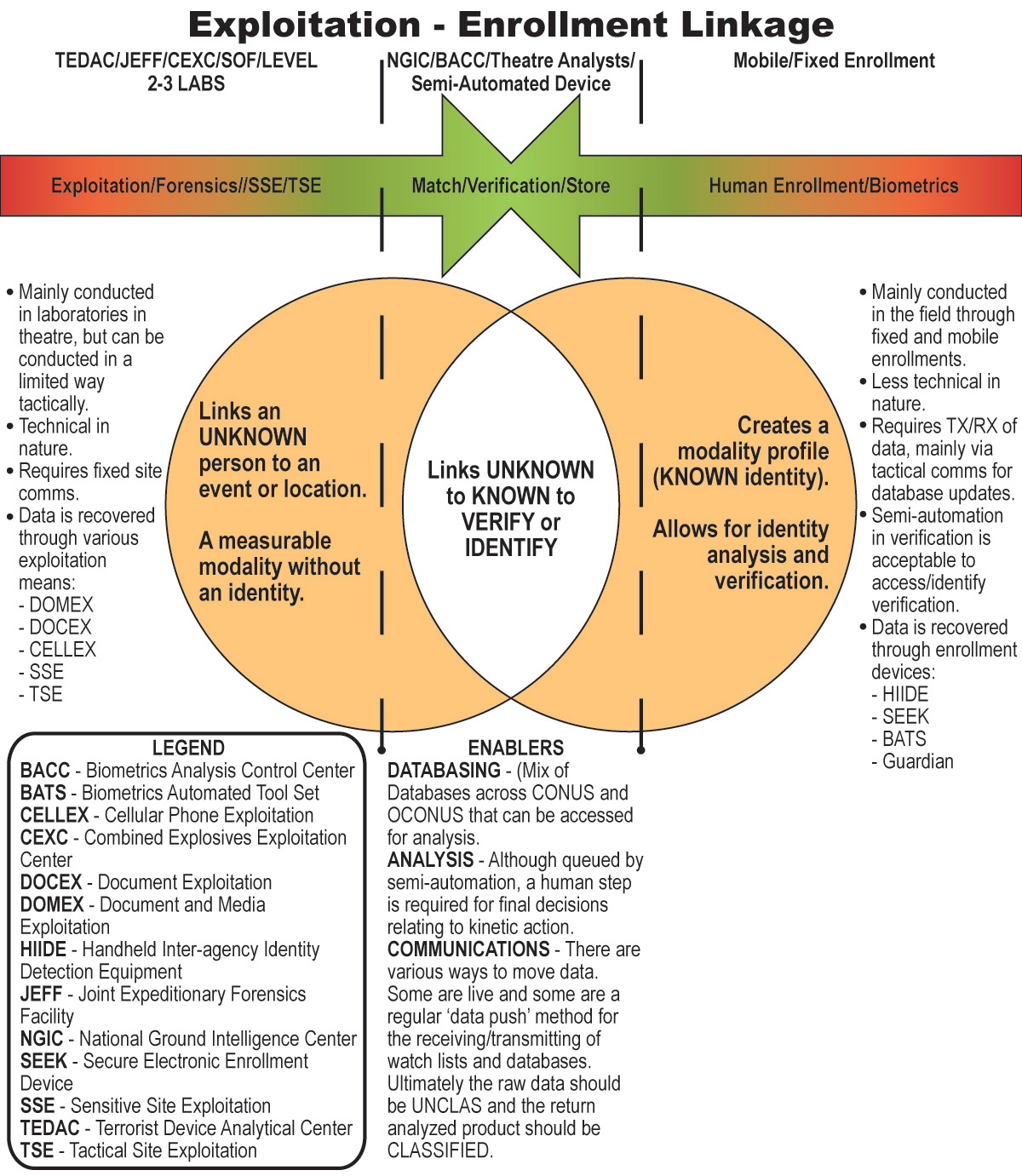

A figure from the U.S. Army Commander’s Guide to Biometrics in Afghanistan explaining the linkage between exploitation of biometric information and enrollment on the battlefield.

Even when it is obvious that the people being enrolled have no connection to the insurgency, the Commander’s Guide to Biometrics in Afghanistan emphasizes that “all collections are important.” The guide states that identification of the “population in a particular area is essential to effective counterinsurgency operations” and essential to a unit’s capacity for “owning ground” in a combat zone. Units must know “who lives where, who does what, who belongs, and who does not.” Mapping the “human terrain” is described as key to security, allowing U.S. forces to know “who they are, what they do, to whom they are related” and to help “separate the locals from the insurgents.” To aid this effort, the guide recommends demonstrating the “value of biometrics” to subordinates and having a “belief in biometrics” so that the “support staff and leaders do not treat biometrics operations as a check-the-block activity.”

Obtaining Convictions

While biometrics are best known for helping U.S forces identify and locate suspected insurgents in Afghanistan, battlefield forensics has become an increasingly important part of the Afghan justice system, helping to convict individuals of aiding the Taliban by hiding weapons caches or constructing roadside bombs. The U.S. Army’s guide notes that forensics are “being used at an increasing rate by the Afghan criminal justice system, and convictions are now occurring in the Afghan courts based solely on biometric evidence.” The U.S. Army’s Afghanistan Theater of Operations Evidence Collection Guide advises soldiers on how to collect various forms of biometric evidence for forensic investigators to provide to Afghan prosecutors in the hopes of obtaining a conviction. This reliance on criminal convictions is part of a “transition from law of war-based detentions to evidence-based criminal detentions” where U.S. and coalition forces must “coordinate with the relevant local, provincial, or national prosecutors and judges to determine the specific type and amount of evidence deemed credible” by providing “evidence and witness statements for use in an Afghan court of law to enable the National Security Prosecutor’s Unit (NSPU) or a provincial criminal court to prosecute and convict criminal suspects.” The guide advises soldiers to “enroll all subjects on-site” following a criminal activity and “ensure that a full enrollment is collected, to include iris scans, ten digit fingerprints, a full facial photograph, and other biometric data.” Complex instructions are included on collecting latent fingerprints from pieces of evidence and collecting DNA samples from potential suspects. The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Guide to Evidence Collection also contains similar instructions including how to make plaster casts of footprint and tire tracks to provide to investigators.

A summary of the conviction of an Afghan man last year for building and emplacing improvised explosive devices (IEDs) that was based entirely upon biometric evidence.

A study in the January 2014 issue of National Defense University’s Joint Force Quarterly found that Afghan courts are increasingly looking for “biometrics as a component of the prosecution’s case.” Focusing particular attention on the Afghan National Security Court located at the Justice Center in Parwan (JCIP), which is described as a “model for successful use of biometric evidence in criminal prosecutions,” the study describes the “prominent role” that biometrics now play in obtaining convictions at the facility. In fact, the Afghan National Security Court has obtained convictions in “almost every case where a biometric match has been made between the defendant and the criminal instrument.” The study also found that sentences are consistently longer for individuals convicted using biometric evidence like fingerprints or DNA. “Collections and enrollments matter and increase the effectiveness of all other operations” the authors state at the conclusion of the study, instructing their readers to “treat every event as a means to collect additional biometrics.”

The number of convictions in Afghan courts based solely on biometric evidence is unknown, as is the accuracy of the systems used for determining a biometric match. However, we do know that the number of prosecutions is going up. One such example is the case of Mohammad Zahid, the twenty-two-year-old man arrested in Khost Province in February 2012. Zahid was arrested with nothing on his person. He claimed to be a student and said he had no connection with the Taliban, yet a latent fingerprint from an IED found in a cache the previous year along with cell phones, battery packs and other bomb-making supplies reportedly matched his own. Zahid was one of over a hundred military-age males enrolled in that village in Khost on February 23, 2012. Now, he will spend years in prison and, according to his testimony, does not know why his fingerprints were found on the bomb-making equipment discovered by coalition forces.

No comments:

Post a Comment